- classic-bridging

- Author: Jonathan Haack, Haack’s Networking

- Instances:

- netzion.haacksnetworking.org (Brown Rice)

- mail.haacksnetworking.one (Pebble Host)

- Email: webmaster@haacksnetworking.org

//classic-bridging//

Latest Updates: https://wiki.haacksnetworking.org/doku.php?id=computing:classic-bridging

This tutorial is for Debian users who want to create network bridges, or virtual switches, on production hosts. By production hosts, I mean something that’s designed to run virtual appliances (VMs, containers, etc.). This tutorial assumes you have access to PTR records and/or have a block of external IPs. In this tutorial, I’ll break down two differing setups I use. To be clear, the tutorial is about much more than bridging, it’s just that the bridges are the most important part because they route incoming url request to the appliances. The first setup, at Brown Rice, is a co-located server. The second setup, at Pebble Host, is a “Dedicated Host,” which means the company provisions actual hardware on your behalf, and drops it in a server shed. Dedicated Hosting is a step above VPSs because they are not virtualized hosts on shared pools; they are dedicated machines. Pebble Host does not offer machines with as much compute as I can afford and provision myself, however, they are still large enough for smaller virtualization stacks. Here’s the technical specifications for each host:

- Brown Rice: Super Micro (Xeon Silver), 384GB RAM, 10.4TB zfs R10 JBOD (Co-Located)

- Pebble Host: Ryzen 7 8700G, 64GB RAM, 2TB NVME (Dedicated Hosting)

I prefer to use virsh+qemu/kvm on the physical host, or bare metal of the server. For my machine in Taos, I run the Debian host OS on a separate SSD on a dedicated SATA port that’s not part of the SAS back-plane. At Pebble, I don’t have this luxury; everything runs on the boot volume. This limitation fits the use-case, however, as I only have Pebble setup to run 5-7 virtual appliances, while the server co-located at Brown Rice has upwards of 30 virtual appliances. Each location, however, has a different set of requirements due to how they broadcast IP/prefixes, whether they filter traffic or not, and how they allocate IPs. For example, Brown Rice treats the prefixes/blocks they provide me as public and, according to that logic, everything is open and exposed. The onus of responsibility on using the server legally and fairly rests exclusively on the client. Since their entire co-located infrastructure fits in one 800 square foot room, with at most 6 full racks, the chance of conflict is negligible. Pebble Host, on the other hand, offers hosting services to over 50K clients. Although the theoretical ceiling of MAC addresses, in and of itself, provides enough combinations (280 trillion +), the reality is that vendors, e.g., virsh, leverage addresses solely within their Organizationally Unique Identifier (OUI), which limits the unique addresses to about 16.7 million (varies by vendor, that estimate is for virsh). Therefore, once you have around 500 or more clients, you start to have a non-neglible chance (1%) of conflict. Since Pebble Host likely has over 50K clients, conflict alone is a reason to filter by MAC address. There are, of course, other reasons to filter, e.g., security, compliance, accountability, possibly GDPR, etc., but it’s worth noting that filtering is a technical and practical requirement for Pebble Host.

Brown Rice Setup

The SuperMicro has a built-in 10Gbps NIC, with 4 ports and 1 IPMI port. Before we start tinkering with the operating system on the host, we need to establish A, AAAA, SPF, DMARC, and PTR records for the host. After that, we will setup IPMI access in the SuperMicro’s BIOS. At Brown Rice, my machine has four cables plugged in, allocated as follows:

- Interface 01: enp1s0f0, has a dedicated cable (IPv4) just for the physical host

- Interface 02: enp1s0f1, has a dedicated cable (IPv4) just for bridging IPv4

- Interface 03: enp2s0f0, has a separate cable (IPv6) just for bridging IPv6

- Interface 04: enp2s0f1, empty

- Interface 05: IPMI; setup via American Megatrends BIOS, access is source-IP restricted

Okay, to setup IPMI, you need to start up your production host and tap whatever keyboard shortcut is required after it POSTS. SuperMicros of this vintage use American Megatrends BIOS. In the BIOS, we need to configure the following:

- Establish the network interface

- Turn off non-essential services in the BIOS

- Create a firewall rule in the BIOS to limit IPMI access to trusted IPs

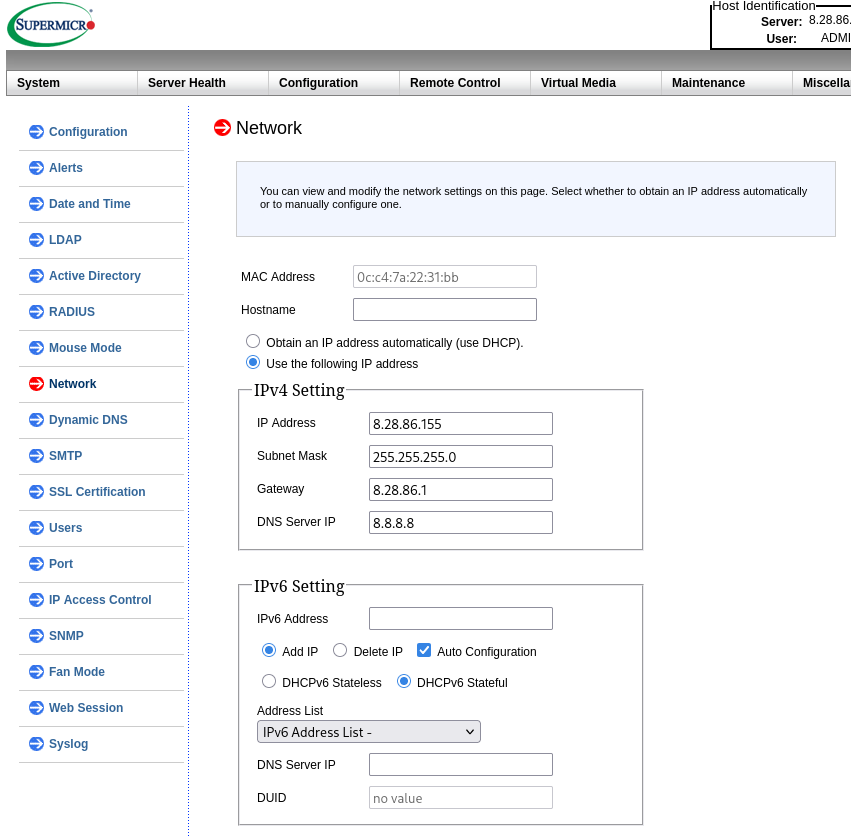

To setup the network interface, navigate to Configuration > Network. After that, enter in your network interface information. Here’s how my configuration is setup:

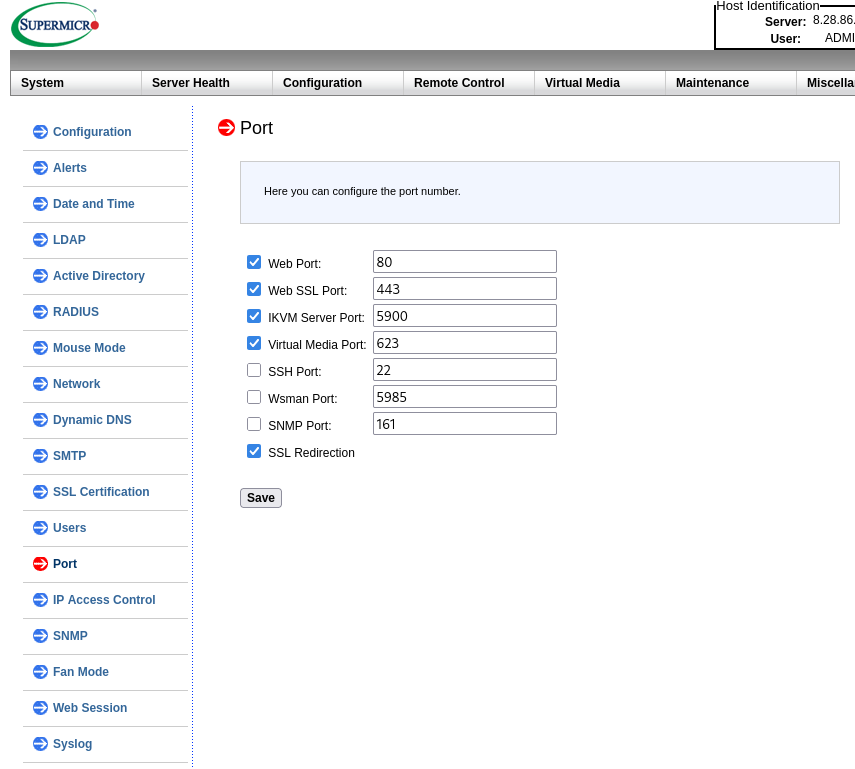

After establishing that, you should use your laptop to try to reach the IP. If it works, then proceed to hardening the BIOS. Hardening involves the two steps mentioned earlier, i.e., turning off non-essential services so they aren’t listening publicly (Configuration > Port). Here’s what that looks like:

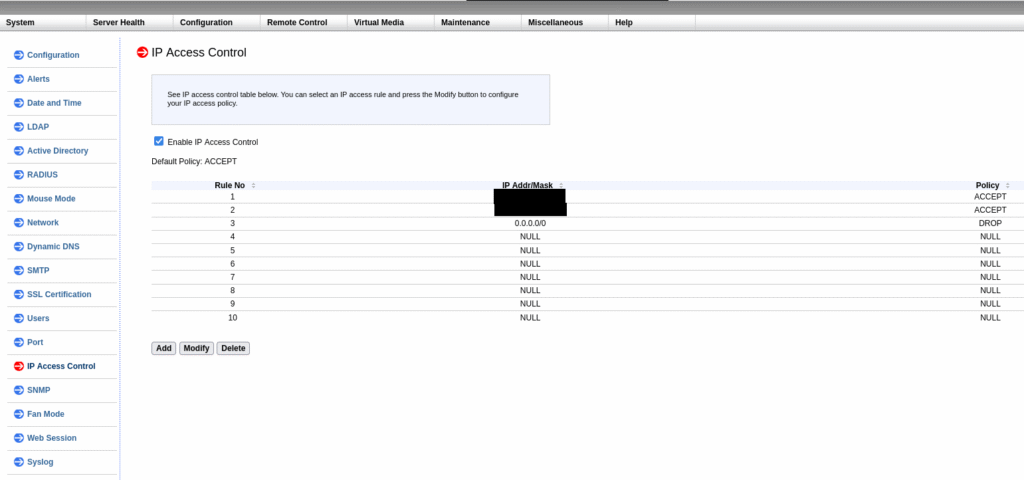

The main thing to ensure is that ssh is turned off. I would only keep that on if you plan to maintain your BIOS regularly and fully understand how it uses the ssh stack. Since I don’t intend to ssh into my production host’s BIOS, I simply keep it off. Optionally, you can also turn off the iKVM Server Port and the Virtual Media Port until you need them. I am not monitoring my production host with external tooling, so I also keep SNMP turned off. Once that’s hardened, let’s create a source IP firewall rule (Configuration > IP Access Control) to limit access to a dedicated and trusted IP.

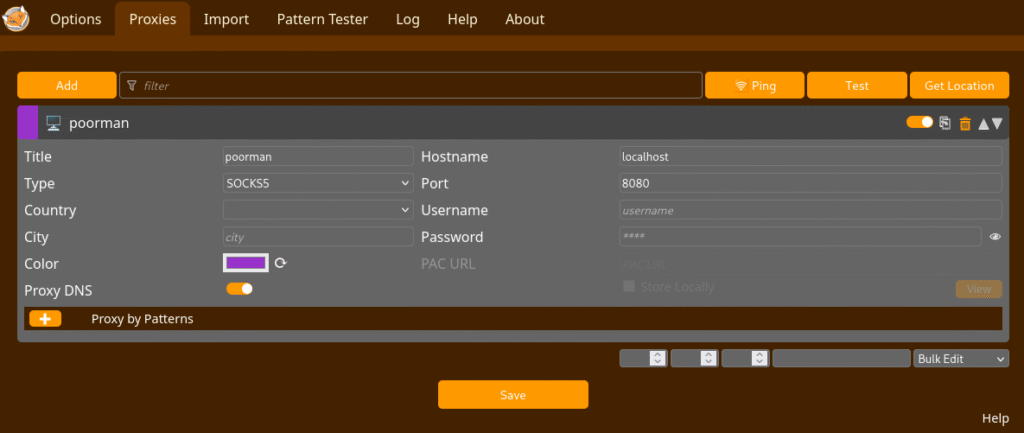

By adding the 0.0.0.0/0 with DROP specified at the end, you are specifying that all other requests besides the whitelisted requests above it, should be dropped. The blacked out entries should be replaced with your approved external IP, e.g., 98.65.124.88/32. The rules are processed in order, top to bottom. In order to “appear” to be using the whitelisted IP, I use a very tiny VPS from Digital Ocean and I proxy my traffic through the VPS using the FoxyProxy plugin. To do this, create a configuration in FoxyProxy that uses SOCKS and listens on localhost on port 8080. Once that’s done, just ssh into your VPS with the -D 8080 flag and port specified, and your web browser will run its traffic through the IP of the VPS, thus allowing you to access the firewalled IPMI panel. This is also very useful for many other cases where you might want to keep your traffic away from prying eyes.

NOTE: I am not concerned about the self-signed TLS certificate due to the source IP and other hardening measures. One can, however, optionally configure this if they so desire.

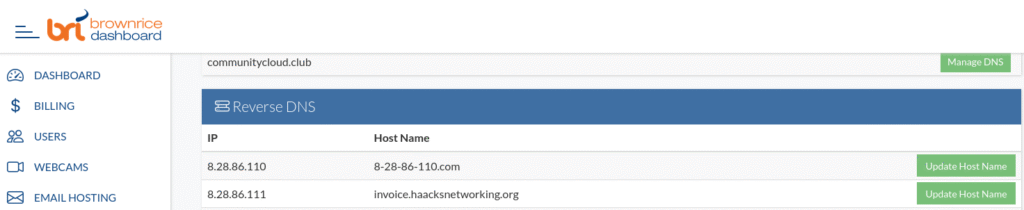

Your primary DNS records should already be setup and caching. Teaching folks how to create primary DNS records is outside this tutorial’s scope. However, many folks reading this might be entering co-located and/or dedicated hosting space for the first time. For that reason, you might not be familiar with what setting PTR records looks like. This is handled by whoever provides the IPs to you because only the owner of the IP block can prove ownership of the IP. In Brown Rice’s case, they also offer and sell IP-space. Even better, they offer a billing and control panel that allows you to establish and manage your PTR records:

At present, the Brown Rice PTR web panel only allows customers to establish PTR for IPv4, however, they allow customers to email IPv6 PTR requests, which I’ve also completed. So, at this point, the primary DNS records and the IPMI networking stack should be live and hardened. Now that’s done, it’s time to setup the Debian operating system on the host. This tutorial assumes your production host is already setup with its zfs/RAID arrays, JBOD, boot volume, SAS backplane, etc., and/or all the other goodies you need or want for your host. It also assumes that you either already installed Debian or you are just about to. If you have not installed Debian yet, make sure to install it with only core utilities. This will ensure that NetworkManager is not installed by default. If you already installed Debian, make sure to remove NetworkManager with sudo apt remove --purge NetworkManager or reinstall Debian, this time without the bloat. The installer might prompt you for nameservers, and if so, use a public recursive DNS resolver (Cloudflare, Google, etc.). If the installer did not prompt you for nameservers, your first task is to specify them in /etc/resolv.conf where, for example, you enter nameserver 8.8.8.8. Now that the OS knows what server to query for DNS entries, we can shift our focus to connecting the production host to the internet. To do that, we will configure the first interface. Open up /etc/network/interfaces and establish your primary interface:

auto enp1s0f0

iface enp1s0f0 inet static

address 8.28.86.100

netmask 255.255.255.0

gateway 8.28.86.1

nameservers 8.8.8.8Once that’s done, you should sudo systemctl restart networking and then run ping4 google.com and ensure that you are routing correctly. If you can’t ping Google, then you need to stop and problem solve further before proceeding. Once that’s done, we can now focus on setting up the other interfaces. First, let’s raise the dedicated interfaces for the IPv4 and IPv6 bridges. Remember, the production host can already be reached via IPv4 on the primary interface, so it’s not necessary or recommended to assign these interfaces addresses.

#bridge ipv4

auto enp1s0f1

iface enp1s0f1 inet manual

#bridge ipv6

auto enp2s0f0

iface enp2s0f0 inet6 manualThis raises both interfaces for the production host operating system and specifies which networking protocol each interface is using. It also instructs that OS that these interfaces are manually configured. Next, we need to bind these interfaces together into a bridge and then assign the bridge an address. Since the IPv4 and IPv6 routes are on separate cables, we do not want to try to assign the bridge more than one address, as this could cause loops and/or break routing. You can safely do this when both protocols are on one layer 1 cable, but not when they are segregated. For that reason, we will only assign one address for the bridge. Please note that we already assigned the primary interface an IPv4 address. This means the production host is reachable via IPv4 already. So, for that reason, it makes sense to assign an IPv6 address to the bridge. This is not only required since they are different cables, but it additionally makes the production host IPv6 reachable. Although its entirely possible to configure the production host to pass IPv6 traffic upstream to the VMs without itself being IPv6 reachable, this is silly and makes no sense. It’s helpful and practical to be able to reach the production host via both protocols. Alright, now that we understand the topology, let’s install bridge utilities, create the bridge, and then raise the interface.

sudo apt install bridge-utils

brctl addbr br0Now that the bridge utilities are installed and the bridge is created, we will raise the interface. To do that, we need to enter the bridge interface configuration in /etc/network/interfaces and then restart networking:

auto br0

iface br0 inet6 static

address 2602:fb41:0:11::2/64

gateway 2602:fb41:0:11::1

bridge_ports enp1s0f1 enp2s0f0

accept_ra 2

bridge_stp off

bridge_fd 0Once this is saved, let’s restart networking with sudo systemctl restart networking. Now that IPv6 is activated, let’s ensure it’s functional with a small ping6 google.com test. Don’t proceed unless this works. Additionally, it would be wise to do another ping4 google.com to ensure that we did not break IPv4 in the steps above. So long as both of test work, we can proceed. If not, use ip route and/or ip -6 route and traceroute and try to determine the cause of the problem. Once everything is working, we are almost ready to configure the VMs. Before that, however, we need to discuss services, listening, and/or hardening of the production host. The question is: do we use a firewall? In my case, I choose to use a firewall. However, I do so not as a substitute for a proper configuration but as a safeguard against mis-configurations and/or mistakes I might inadvertently make. Many folks don’t do this and instead just slap a firewall on hosts and don’t bother checking configurations. For example, I once reviewed a server where the sysadmin was unknowingly running publicly exposed samba (SMB) on a production host. In this case, the firewall was prohibiting access, which although helpful … is not the proper solution. The proper solution is disabling the service in the first place. This is what I mean by using firewalls as extra protection but not as substitutes for properly configured hosts. So, how does one do this? That’s simple, you check what services are running with ss -tulpn and/or the classic netstat -tulpn. Make sure that everything you see there is something you setup and, if not, turn it off or determine why it’s safe to listen. In my case, I do this in addition to turning on UFW. For me, it’s both/and, but – to be clear – there’s little to no risk if you simply manage your services properly. Here’s how I configure UFW:

sudo apt install ufw

ufw allow 1194/udp

ufw allow from 192.168.100.0/24 to any port 22 proto tcp

ufw enableThis UFW setup presumes you have a properly configured VPN server running on the production host. If so, it allows ssh only from the VPN’s dedicated subnet. Obviously, this is not strictly required. If you do use this approach, use a non-standard subnet so that you can provide extra protection against brute force attempts via obfuscation. If you don’t want to put the production host behind a VPN, then you can optionally expose ssh publicly. It goes without saying that one should only be using ssh keypairs, not passwords. To do the simpler setup, use the following:

sudo apt install ufw

ufw allow 22

ufw enableThat’s all you need. Remember, if you need emergency access to the host, you use IPMI for that, which is not part of the host’s operating system. This is the traditional approach whereby you never expose the production host on anything besides ssh or openvpn. Alternately, you can use Cockpit or Proxmox, which expose the server to the public over 80/443. If you go this route, make sure you have TLS setup properly and use 18+ character passwords with appropriate complexity. That might be a bit overkill, but better safe than sorry. Okay, the last thing we need to do is turn on packet forwarding in UFW, which is disabled by default:

sudo nano /etc/default/ufw

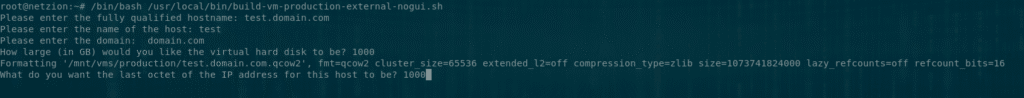

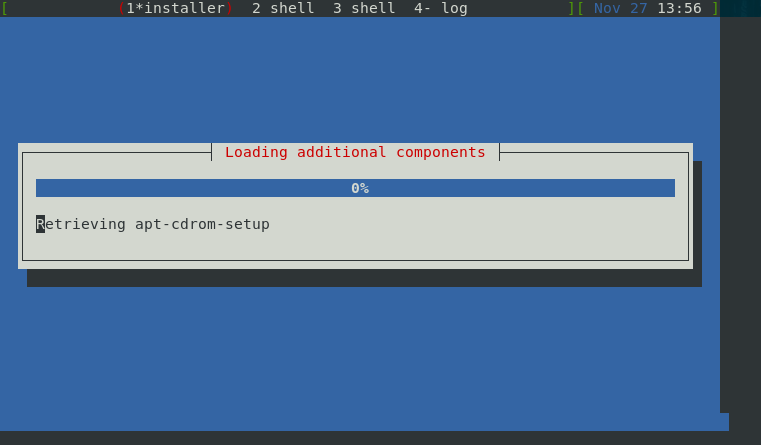

DEFAULT_FORWARD_POLICY="ACCEPT"Our production host is now sufficiently hardened and our firewall tooling will allow the bridge we created above, to forward packets upstream to virtual appliances running on the host. This means we can now setup a virtual appliance. In my case, I prefer VMs over containers, pods, docker images, etc. I find most of the performance benefits to be neglible and I don’t want to sacrifice control or integrity to docker image maintainers. I certainly don’t want to learn another abstraction language, i.e., docker-compose, in order to both maintain the underlying system in addition to docker. VMs provide near-equivalent performance, isolated kernels, and full control over the OS. It might be overkill for some smaller services/instances, but the benefits far outweight the drawbacks. Now, when I first began this project, I used ssh -X user@domain.com to log into the host, and then would run virt-manager on the host, which passed over X11 to my desktop. This is archaic, slow, and inefficient. As I was not ready to hand over control to Cockpit or other tools, I dug deep into preseed.cfgs, Debian’s native auto-installer. After some work, I was able to create a fully automatic way to install new VMs – with desired networking and/or other parameters – within the shell of the production host. That approach is covered in detail in this blog post. I recently revised these configs and scripts to work with Trixie and everything is purring. It takes roughly 5 mins to build a new VM. Here’s what this setup looks like:

That ncurses installer is not being passed over X11. That’s running inside the shell of the production host using a TTY argument that I passed via virsh. In my case, I pass the ssh keys to the VM with the preseed. I also configure repositories, networking, install qemu-guest-agent, and other tools the VMs need. Additionally – and this is a crucial step – I also attach the VM’s virtualized NIC to the bridge I created above, br0. Although the preseed tutorial is outside the scope of this tutorial, I’ll share the virsh command I use – within the greater build script – to populate the VM:

virt-install --name=${hostname}.qcow2 \

--os-variant=debian12 \

--vcpu=2 \

--memory 4096 \

--disk path=/mnt/vms/production/${hostname}.qcow2,driver.discard=unmap \

--check path_in_use=off \

--graphics none \

--location=/mnt/vms/isos/debian-13.1.0-amd64-netinst.iso \

--network bridge:br0 \

--channel unix,target_type=virtio,name=org.qemu.guest_agent.0 \

--initrd-inject=/mnt/vms/cfgs/external/${hostname}/preseed.cfg \

--extra-args="auto=true priority=critical preseed/file=/preseed.cfg console=ttyS0,115200n8"If you don’t want to tinker with preseed, you should at least consider running virt-install with preconfigured options. It saves time and avoids janky pass-through. At this point, your VM should be built, have ssk keys exchanged with it (or populated with the preseed), and be ready to configure. Since my preseed passes the IPv4 interface configuration into the VM, I only need to add IPv6 connectivity. (I am currently working on adding IPv6 pre-population to the preseed script.) Once you shelled into the VM, let’s open up /etc/network/interfaces and add the IPv6 interface. Or, if you have not yet built the preseed stack and/or not yet mastered virt-install, you can optionally use X-passthrough to open the virt-manager console and manually enter the interface configurations. Regardless of how you do this, you should have something like the following setup in the VM’s interface file when you are done:

auto enp1s0

iface enp1s0 inet static

address 8.28.86.122

netmask 255.255.255.0

gateway 8.28.86.1

nameserver 8.8.8.8

iface enp1s0 inet6 static

address 2602:fb41:0:11::24/64

gateway 2602:fb41:0:11::1At this point, run ping4 google.com and then ping6 google.com inside the VM. If you did everything right, both will respond in kind. So, now that this is all configured, I can spin up VMs and the associated instances within minutes! That’s all you need to do! ;O

Pebble Host Setup

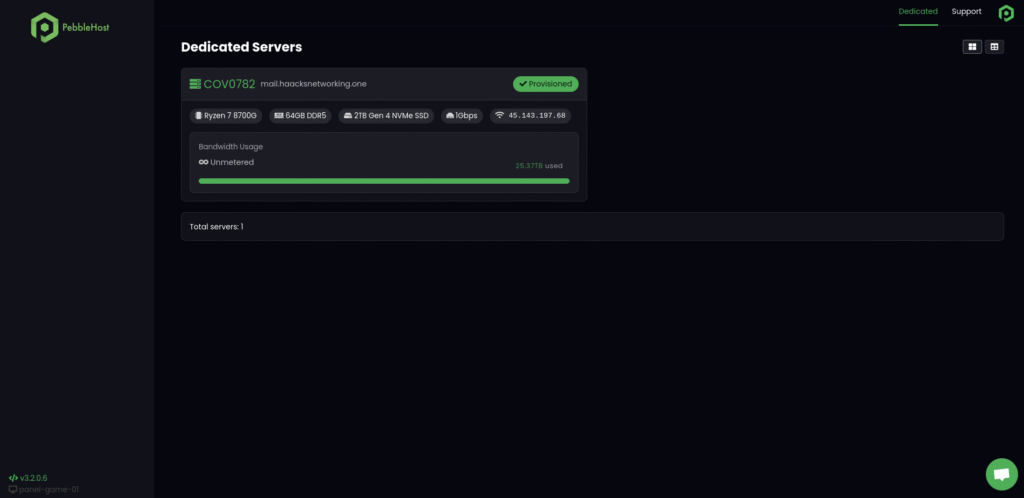

In most ways, the Pebble Host setup is simpler. I don’t need to setup IPMI because they have a domain controlled and public facing web panel that they use to route external url request to the client’s IPMI panel. This is common for hosting providers, of course. Here’s what their web panel looks like:

This is merely a front end to their IPMI implementation. They recently upgraded it and it’s very clean. Most importantly, this web panel includes DNS and networking management, which we’ll need for PTR records and managing VMACs.

- We need to establish PTR

- We need to manage and clone VMACs that comply with their MAC address filtering

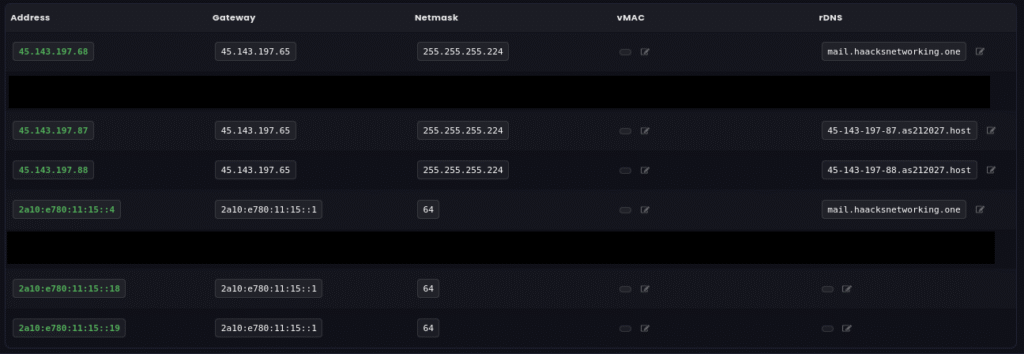

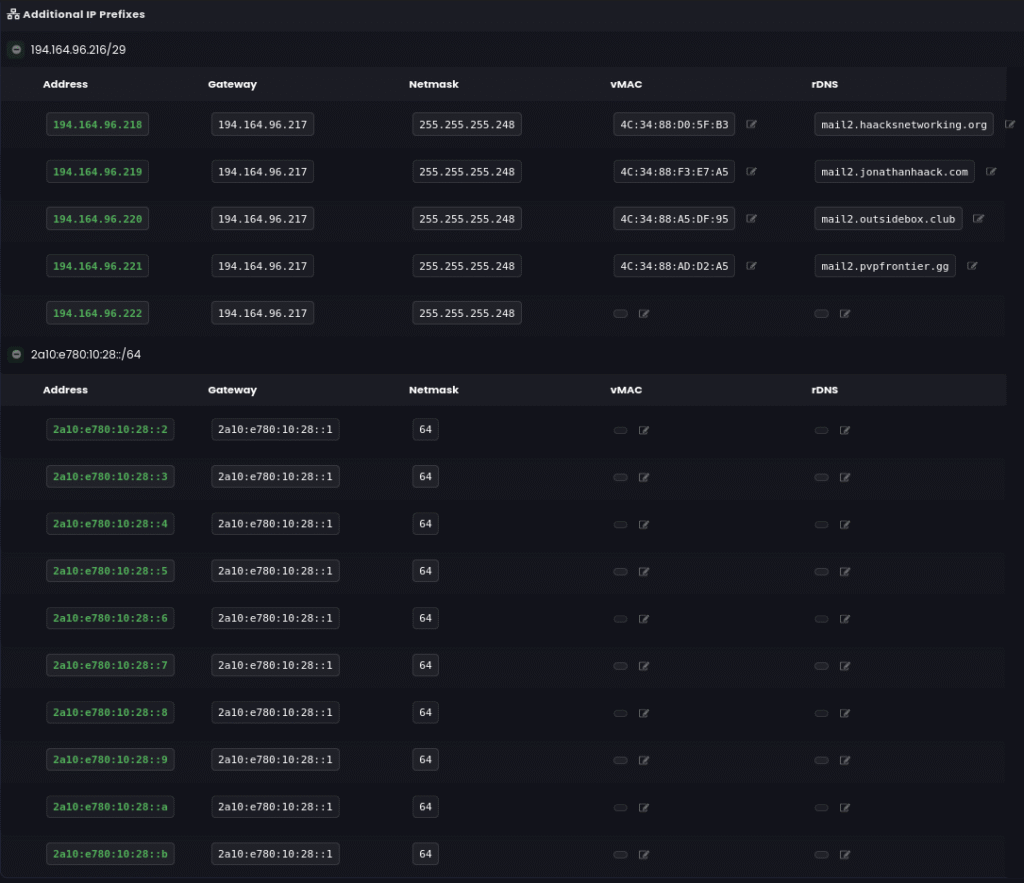

A VMAC is a virtual MAC, which they use both to filter traffic, and presumably, to avoid potential MAC address conflicts that have a very high liklihood of occuring in a topology of their size, or roughly 50K clients or more. I’ll note that the networking and PTR panel is also very clean, allowing easy configuration for each IP address and its associated VMAC. Here’s a peak:

In my case, I purchased a few additional IPs, so you can see those differing prefixes below. When I first began hosting with Pebble Host, they were not fully IPv6 active. However, about a year ago, they added IPv6 support and it automagically populated in this lovely web panel. Accordingly, you can see that I have PTR setup, for both IPv4 and IPv6, on the dedicated host, mail.haacksnetworking.one. The other IPs besides mail.haacksnetworking.one are either in use for clients, reserved and waiting for allocation, and/or being used for testing servers I am working on. For example, you can see a slew of mail servers at the bottom, which I am slowly working on and intend to run doveadm and therefore serve as backups to my primary selfhosted email servers. But, I digress … let’s continue discussing the stack and setup requirements instead of what I use the stack for! So, once you purchased your dedicated hosting package, you get something like my above screen shots. Once that’s done, and you can shell into the dedicated host and have made sure ssh keypair auth is enforced, we can configure the interfaces file. Remember, they drop both IPv4 and IPv6 on one cable/interface and IPMI, routed through their web panel, on the other interface:

- Interface 01: enp4s0, has a dedicated cable (IPv4 and IPv6) for the dedicated host

- Interface 02: IPMI and web-panel (managed by Pebble)

They do not build the virtualization stack for you – you have to do that. So, you will be replacing their stock interfaces file with your own configuration. Make sure you’ve installed bridge-utilities, created the br0 bridge, and then do something like the following:

# Establish both interfaces

auto enp4s0

iface enp4s0 inet manual

iface enp4s0 inet6 manual

# Establish bridge and ipv4 and ipv6 addresses

auto br0

iface br0 inet static

address 45.143.197.68/26

gateway 45.143.197.65

dns-nameservers 8.8.8.8

bridge-ports enp4s0

bridge-stp off

bridge-fd 0

bridge-hw enp4s0

up ip route add 45.143.197.86/32 dev br0

up ip route add 194.164.96.218/32 dev br0

iface br0 inet6 static

address 2a10:e780:11:15::4/64

gateway 2a10:e780:11:15::1

bridge-ports enp4s0

bridge-stp off

bridge-fd 0

up ip -6 route add 2a10:e780:11:15::17/128 dev br0

up ip -6 route add 2a10:e780:10:28::2/128 dev br0

Now, in Pebble Host’s topology, IPv4 and IPv6 are both on the same physical layer cable. This means we can safely assign both IPv4 and IPv6 addresses to the same bridge without issue. Also, for reasons not entirely clear to me, their topology requires users to push the routes to the VMs inside the dedicated host’s interface file. I’ve tested the stack without these routes and they don’t work. I’m not privy to their entire network stack, but it makes sense generally. Since it’s a filtered and managed network, they don’t allow “rogue nodes” to connect directly to the assigned gateway. You have to publish the route yourself. After that, they check requests to the gateway against the approved VMACs and drop all other requests. Again, their topology is not published publicly, but this seems to be what’s going on under the hoods. Going back to the above interfaces block, it should be noted that although most of this configuration is standard, there’s one additional line that’s hard required and less common. That is, bridge-hw enp4s0 line must be specified in the bridge configuration stanza. It only needs to be entered in one block, but entering in both won’t hurt anything. This tiny line ensures that bridge itself has the same MAC address as the pre-configured and approved MAC address of the primary interface. Without this line, the bridge will auto-generate its own MAC address via iproute2 tooling, and since that MAC is not approved by Pebble’s topology, the bridge will not pass traffic. This took a good week to figure out, but it makes sense. Pebble has a large topology and massive client base; they got everything monitored and locked down. At any rate, once this done, we can now spin up a VM on the dedicated host. Similarly to the Brown Rice setup, I ported my preseed and virt-install scripts over to the Pebble Host instance which made installing VMs a minutes-long process. If, however, you want to use X-passthrough, make sure to edit their /etc/hosts file. For whatever reason, they don’t populate the hosts file properly and X-passthrough won’t work without it!

127.0.0.1 localhost

127.0.1.1 mail.haacksnetworking.one haacksnetworking

# The following lines are desirable for IPv6 capable hosts

::1 localhost ip6-localhost ip6-loopback

ff02::1 ip6-allnodes

ff02::2 ip6-allroutersUse something like I provided above, but adapted to your use-case of course. Now, I have no idea why they put a non-standard hosts file in place, but regardless, it’s your dedicated host to properly configure as you see fit. I’ll let you know, however, that it took me a week or so to realize why X-passthrough was not working. So, I hope sharing this helps anyone still using those legacy install and management tools. At any rate, once your VM is installed, you need to change its MAC address to match the VMAC address in the Pebble Host web panel. To do that, shutdown the VM and then edit it with something like virsh edit vm.qcow2. Once inside the .xml file, find the line that begins with “mac address” and edit the address to match the VMAC. Make sure the VMAC address for the VM is different than the dedicated and pre-assigned VMAC for the dedicated host. The web panel has a generate option, where you can make VMACs at will. Again, it is presumed that you already connected the VM’s NIC to the bridge during the installation of the VM. In summary, we’ve ensured that:

- The bridge, br0, has a matching MAC address as that of the dedicated host’s primary NIC

- The VM has been connected to br0

- The VM’s NIC has been changed to match the approved VMAC address specified in the panel

Once this is done, restart your VM and try to log in. If you did not setup preseeds with virt-install that auto-populate your interface, then use X-passthrough on the dedicated host, along with the virt-manager console, and type in the interface configuration manually. Again, in my case, the preseed passes my interfaces file into the VM so, as soon as it can route, I can reach it via ssh. As I mentioned earlier, I don’t yet have the preseed configs setup to pass IPv6. So, I enter that information manually after connecting via IPv4. However, at the end of the day, your VM should have something like the following:

auto enp1s0

iface enp1s0 inet static

address 45.143.197.87/32

gateway 45.143.197.65

nameservers 8.8.8.8

iface enp1s0 inet6 static

address 2a10:e780:11:15::4/128

gateway 2a10:e780:11:15::1Once you’ve got something similar inside your VM, drop the ping4 google.com and ping6 google.com tests inside it and make sure everything is routing properly. If so, you got it working and can now spin up and/or scale to more VMs to your heart’s content.

Thanks,

oemb1905

Happy Hacking!